Exhibitions and events

EVENTS AND EXHIBITION

Onsite Exhibition

Online Exhibition

DUYAN ANG KADAGATAN (CRADLED BY THE SEA): Cebuano Culture And The Heritage Of The Sea

To think of Cebu as aquapelagic is to look at it beyond its islandness, beyond the terrestrial geography that defines it as a place, a province and a community. Rather, the important notion of the aquapelago offers an alternative metageographical framework that emphasizes the often negligible aquatic spaces between and around mainland Cebu, its smaller island communities and its neighboring island provinces, and how these waters are utilized and navigated in a manner that is fundamentally interconnected with and essential to the social and cultural life of Cebuanos.

Duyan ang Kadagatan, cradled by the seas, explores the important place of Cebu’s surrounding waters in shaping Cebuano culture and identity. The national artist Resil Mojares traces the origin of the name Cebu to the word “sugbo” which means to wade through shallow waters as one alights from a boat upon arriving at the shoreline. To sugbo through the waters is to be at the crossroad of exchange, to be at the gateways of a new beginning. The very idea of sugbo aligns with the idea of Caribbean historian Kamau Brathwaite’s theory of “tidalectics,” an analytical method based on what he describes as “the movement of the water backwards and forwards as a kind of cyclic motion, rather than linear.” The seas mediate places, the waters enchant time, dance with the winds, and deliver people and cultures from shore to shore.

The etymology of Sugbo comes as no surprise as the history of the Cebuanos is hugely linked with the movements of the tides, of the knowledge of the sea, of stories of long voyages of ancient sea-faring Visayan warriors. As early colonial chroniclers had recorded, Cebu was a bustling international port that serves as the center of social, economic and cultural life of precolonial Visayan society.

The exhibition, therefore, allows for a postcolonial reimagination of Bisayan culture by re/turning to its origins in islandic life that held a land-oceanic continuum, that situates Cebuano social life in an integrated terrestrial-marine space. Furthermore, it hopes to examine the inevitable influence of long colonial subjugation that defined the Philippine archipelago as territories and satellites of colonial presence in this part of the world. The exhibition studies the island communities of Zaragoza islet in Badian, Olango, Camotes, Hilotongan and Bantayan islands, exploring various aspects of islandic cultures including boat-building traditions, fishing methods, and implements, intangible knowledge like sea routes, fishing seasons and ethnoastronomy, faith, and belief systems. It explores Cebuano's creativity and ingenuity expressed in the communities’ foodways, boat designs, and shellcraft. Above all, it highlights the heroism of local fisherfolks in ensuring marine food security and protecting the seas amidst growing ecological concerns.

The idea of aquapelago is to allow the waters to speak, enchant us again with its stories, reveal its secrets and troubles, and ultimately endow us with a kind of eco-consciousness, to think with water as a step towards rediscovering and harnessing the cultural knowledge of island communities to mitigate pressing environmental concerns.

Jay Nathan

Jore Curator

Onsite Exhibition

Online Exhibition

DUYAN ANG KADAGATAN (CRADLED BY THE SEA): Cebuano Culture And The Heritage Of The Sea

Section 1

PAGSUGBO, PAGLAMBO

Surging Tides of Faith

Cebu’s primacy as a cultural hub hugely depended on the economic activities and cultural exchanges that its port facilitated. As early colonial chroniclers had recorded, Cebu was a bustling international port that served as the center of the social, economic and cultural life of precolonial Cebuano society. Its strategic location at the heart of the Visayas made for an ideal route and trade center where merchants, local and foreign, gathered to engage in trade. In the 1800s, it was declared open to world trade by Spain and continued as a major port in the Philippines during the American colonial period. At present, the Port of Cebu continues to be a major seaport, serving as the homeport of approximately 80% of the Philippines' total domestic shipping industry.

At noon on Sunday, April seven, we entered the port of Zubu, passing by many villages, where we saw many houses built upon logs. On approaching the city, the captain-general ordered the ships to fling their banners.

Cachey Jr, Theodore J., and Antonio Pigafetta. The First Voyage around the World (1519-1522): An Account of Magellan's Expedition. 2007.

The island of Cebu is stark and simple. Long and narrow (its area 1,707 square miles, its length 122 miles, and nowhere does its width exceed 20 miles), it is spined by a saw-toothed central cordillera, running north-south, reaching a height of almost 3,400-feet at its center and gradually decreasing at both ends of the island. The island's coastline is very regular, without embankments, and consists of a series of alternating valleys and ridges reaching down from the central uplands. Narrow and with very little level land, Cebu's distinct settlement pattern consists of elongated towns and villages hugging the coast.

The name Sugbo means "to walk in the water," a reference to how those who came to the settlement by seacraft had to wade ashore as the shallow waters prevented boats from reaching dry land. The name is evocative of arrivals, of the island as destination, connected to points beyond its shores.

Mojares, Resil, and Susan Quimpo. "Cebu: More than an island." Makati City: The Ayala Foundation (1997).

The nineteenth century was a watershed in the urban transformation of Cebu. Shifts in the world economy and Spanish colonial policy led to the opening up of the Philippine countryside to large-scale trading in commercial crops. Cebu was opened as a world port in 1860, ushering in an era of prosperity that had many ramifications - increase in population, influx of Chinese immigrants and Western merchants, rise of new industries and occupational classes, shifts in property ownership patterns, expansion of the colonial bureaucracy, and advances in transport and communications. Cebu reemerged, on a scale greater than before, as commercial hub and transshipment point between the Philippine southern hinterland and the world market. The transfer of wealth from peripheral regions to Cebu created the ground for various phenomena associated with urbanism.

Beyond memory now is the fact that the Cebu port area was once the spatial 'anchor' of the settlement as it was here that such major rivers as the Sapangdaku (Guadalupe) and Kinalumsan, and branches like the Parian River, flowed into the sea. Cebu's maritime and riverine character is still preserved in such place-names as Pasil (sandy beach or river bank), Suba (river), and Tinago (a cove where boats can hide) but the old identities of such districts survive only in their names. The coastline has been radically transformed and rivers have silted, been built over, or have degenerated into dirty esteros or canals (as in the case of Parian).

Mojares, Resil B. "Dakbayan: A cultural history of space in a Visayan City." Philippine quarterly of culture and society 27. (1999)

Section 2

BANSAY-BUGSAY

Cebuano Boat Building Traditions

From ancient times to the present, passed down from generation to generation, the Cebuano’s mastery of the waters is evident in the range of boats that they have built, and for various uses that they have been customized. As seafaring people, the bodies of water were their highways and boat-building skills among the natives were essential. Employing the technologies of the times and harnessing the strength of indigenous timber and materials abundant in local forests, precolonial Cebuanos built boats for transporting people and goods, for fishing purposes, and for raiding expeditions and wars. Local boat construction under a skilled panday (carpenter) showed an advanced system of engineering and construction technology that ensures swiftness, efficiency and safety in navigating the treacherous seas and in harnessing the rich underwater resources.

At present, Cebuano pandays, especially from among coastal communities, continue to engage in boat-building, following traditional techniques, infused with a flair for design. Shipbuilding in Cebu continues to be a major industry with several shipyards that operate and supply worldwide demand for well-built seacraft.

"The Visayan Indians excel in this skill [boat building] for it seems that all of them are born carpenters or Pandayes as they are called here. So even the construction of our galleons which is continual in these islands and necessary ... depends on these [panday]. Only the Visayan Indians without distinction have employment and wages as pandayes or skilled carpenters.... There have been Visayan Indians who have been equal to the Spaniards themselves in knowing how to select and fashion the wood suitable for the ships. They are paid salaries greater than to many Spaniards”

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." Part One, Book, 3) (2002).

Section 3

Karaang Kaalam

Ethnoastronomy, Sea Routes, Fishing Seasons

In cruising the high seas, Cebuanos have created a collective indigenous maritime knowledge that has come through generations over time. It presents a certain way of knowing and understanding how the Cebuanos respond to the interrelations of the sea and land formation. They have studied how the stars could guide them to their fishing grounds, how mountains on the horizon create coordinates in locating places within the vast sea, and how the coming of the winds signals the arrival of a certain variety of fish. Ultimately, this knowledge system reveals the principles and values the Cebuanos hold dear as bearers of this intangible heritage—responsibility, respect, reciprocity and connectivity to each other and the environment.

Various Philippine cultures have long ago formed their own map of the sky by organizing the stars into constellations. They have, thus, claimed the sky as their own and put their own distinctive marks on it. As they made the sky part of their culture, it in turn, influenced the way they think, act and live. Though the colonial interlude brought changes to Philippine cultures, their high regard for the sky and the stars remained, reinforced and enriched by colonial experience.

Balatik and Moroporo are two of the more prominent star groups in the Philippine sky. Philippine cultures have myths that explain the presence of these stars in the sky and their functioris in their lives. They consult them as they go on with their everyday lives as in determining the propitious times for planting, fishing and hunting. Together with the sun and the moon, the stars serve as symbols for ideals and values that these cultures hold on to.

Ambrosio, Dante L. "Balatik: Katutubong bituin ng mga Pilipino." Philippine Social Sciences Review 57.1 (2005): 1-28.

--------------------

These natives believed that winds sprang up in subterranean caverns or caves, as if they knew the ancient tale about the father of the winds, Aeolus. When they opened it, by reason of the larger or smaller opening, they caused greater or lesser breeze to blow. Even today, they are of this opinion.

Although the four most general winds, which are in opposition to the poles of the earth, are recognized everywhere to be the principal ones, they are experienced here each in its own season. However, there is no doubt that each has a very different duration and length of time. So we begin with the east wind, which the Spaniards commonly call here, brisas, and the natives, amihan. There is no doubt that in these islands of the Pintados it is the most common and most persistent and with better qualities.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 2) (2002).

--------

In fishing ventures, they did the same thing; they placed the first fish that they caught, either whole or a portion, on top of some rock or some high place. In this manner, they had appeased the diwata of the sea and hence, would catch an abundance of fish, this way.

When they went out hunting or fishing and if someone should ask for a portion which they call paat, they would go back. This they felt to be an ill-omen because that part caused the boars and the fish to flee. In these matters they had other paglihi, which we shall deal with in the succeeding chapter; these were very numerous and they had one for every occasion.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 3) (2002).

The bounty of wisdom lies within the rich tapestry of interactions between a community and their The bounty of wisdom lies within the rich tapestry of interactions between a community and its natural environment. This local knowledge is a treasure trove passed down through generations, shaping the worldview, identity, and decision-making of the people. It is a unique and valuable asset that outsiders cannot easily access.

Section 4

Dasig sa Pagpanagat

Fishing Methods and Implements

Alongside navigational prowess that enabled Cebuanos to master navigating the surface of the seas, they have come to master harnessing the underwater too. They know every kind of fish and the behavior of such, the sea shells and underwater vegetation, that they harvest as part of their sustenance. To navigate the vast underworld, often mysterious and mythical, and harvest an abundant catch, fisherfolks have developed various fishing techniques and methods. In the same manner, they invented instruments and implements to serve specific ways of fishing that ensure an abundant harvest.

With the changing environment of the sea, new methods have been developed and with the depleting marine resources caused by climate change and overfishing, fishermen have to fish for longer periods, developing techniques that suit day and night fishing, often employing multiple methods to yield sufficient catch to feed their families and to sell to local markets.

Various times when I was traveling there, I accompanied them to see it. It is a matter of great amusement, although it has some danger.

The method is this: on certain days, and they know about the waning or waxing of the moon, the one who is the leader of this fishing expedition sounds his horn. These here are large shells, pitones they are accustomed to call them, or a section of a bamboo of the large variety which they call budiong. Those who wish to go fishing prepare themselves. At times there are thirty or forty balotos (canoes). Each one carries a net two brazas, or a little more, in height and the length of the vessel. They carry two long poles and place one in the prow and the other in the stern along one side or board. There the net is stretched like a sail.

The leader or foreman carries, in addition to this net, another on the side which they call pukot with its sinkers and shell which at the proper time they throw into the sea. He proceeds forward and on discovering a school or an abundance of fish, he gives a signal. All the vessels come together and placed toward the outside the sides or boards where the nets have been set upright, ten or twelve or more arrange themselves to form an enclosure. If there are many, they form two or three groups in a square or round or elongated according to the place and the fish.

Two or three men then get into the water, it is ordinarily done in shallow places and at low tide, and stretch out their nets, not to catch the fish but to scare them. There are various kinds of lisas which they call here balanaw, agwas, taguman and others which leap up on seeing the net below them and on sensing something pursuing them. When leaping, then they bump into the nets which standing upright serve like straw on top of the fences or a wall, and with the impact they fall into the balotos. Everything that falls into the baloto belongs to the master of it except that afterward all gather together and they give one of ten to the one who is the leader. Some, and this depends on their fortune, at times get a great quantity and some nothing because not even one fish fell in their baloto. However, they are so courteous that they give a share to those who caught nothing so that on another day the latter may give them something in return when their own short-lived fortune leaves, like those who had no success on that occasion.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 2) (2002).

In ages past, the ancestors of our land lived in close harmony with the great waters that surrounded them. Their very lives were tethered to the ocean, relying on its bounty to sustain them day after day. Armed with spears, arrows, clubs, and nets, they set out each day with an unshakeable belief that there was an abundance of resources that lay ahead.

As time marched forward, however, the mighty spears that once were used to harvest the seas began to lose their luster. The ocean's creatures grew more elusive. Overfishing and reef destruction contributed to the hardship and imbalanced relationship between nature and fisherfolk. People soon knew that they must adapt if they were to continue thriving in this watery world. With ingenuity and unwavering determination, they turned to their trusty arrows and nets, modifying and refining them to better suit their needs.

Through countless trials and errors, they honed their skills and deepened their knowledge, discovering new techniques and tools that unlocked the ocean's secrets. And so, armed with their newly fashioned equipment, they ventured forth once more, confident in their ability to overcome any obstacle that lay before them.

Section 5

Abot sa Dagat

Cebuano Maritime Foodways

Living with the waters means an abundance of fresh seafood served at any household’s table. The freshness of maritime produce has created a certain flavor profile that characterizes Cebu’s culinary traditions. Fishing communities have mastered ways to grow, gather, prepare, serve and consume food from the sea. They have produced food traditions based on locally available fish and shellfish.

The salt from the sea and the vinegar from the ubiquitous coconut trees become important agents in preserving food delicacies.

To discuss the multitude of fish that these seas hold, would be to probe its depths, count its sands and, above them, the stars are infinite. Many are similar (if not the same) to those that are found in Spain and its seas; others are very different. All are very good, very tasty and more or less healthful depending on their qualities…the uses made of them by the natives, who in general like to eat fish more than other flesh of animals and birds. Perhaps, it is because of the greater affinity which, as islanders and sons and daughters of the sea, they have with them.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 2) (2002).

--------

We are able to say, that it is a specially of these islands that all their seas are of salt because of the ease with which it is made and the quantity and abundance in which it can be, and ordinarily is, made. It is even the major cause for the preservation and perpetuity according to some philosophers.

I find three ways of making salt over here which they call asin, all very different and easy.

The third manner is peculiar to the Bisayas and only they employ it in these islands. For this reason this salt of the third class is called everywhere in the islands 'sal de Bisayas'.

The use of salt among these natives does not consist in putting it into shakers; rather, they place a piece of it whole on the table. They wash it first, lest some dust or soot has become attached to it, for they keep it on top of the hearth in their houses. He who wishes to use it does not break the piece or grind it beforehand, but he rubs this piece over the food. Whether it is rice or various roots, about which we have spoken above, he gives the piece of salt a few soft blows. If it is a liquid dish like a broth, he stirs it around a little with this stick and by this imparts flavor, more or less according to whether he holds it still or stirs it about. That same piece is used by everyone, even though there may be many at the table. It lasts until it is used up and dissolves; they bring in another in its place. This is a custom to which the Spaniards who live here have become accustomed.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 2) (2002).

The Philippines is an archipelago of over 7,600 islands that sits at the heart of the Coral Triangle Region, the global hub for marine biodiversity. It is no surprise that fishing is a vital source of livelihood and sustenance for the country, especially in Cebu, where the surrounding islands are teeming with a bounty of fish and other organisms, fueling the local economy. To preserve these sea treasures and extend their shelf life, we have perfected the art of food fermentation and drying.

In food drying, microorganism growth is controlled through water and moisture removal. In communities, these translate into “buwad”, a food drying method using the heat of the sun.

Fermentation is a process of controlling microorganism growth, using different ingredients. Often this means the use of suka, or vinegar, and spices, like ginger, onions, garlic, and salt. The fermented varieties of fish are referred to based on the specific fish species of different fish parts. These fermentation methods could be the ginamos and the dayok.

The ginamos” is made from fermented small fishes, like Bolinao, Toloy (pino), Lubgas, and Turnos, The with the latter being the most abundant from March to August on Olanggo island. The technique used to catch these fish is called “panapyaw”.

These fermented food are measured in “lapad” or one glass container of a Filipino alcohol drink. The ginamos and dayok are found in the different local marketplaces of the municipalities and cities.

Through their time-honored methods of preservation, the people of Cebu have not only sustained their way of life but also created a unique culinary culture that has become a source of pride and joy for the local community.

(Photo)

The “dayok” is another fermentation method using fish entrails. Usually of the fish Danggit/Rabbitfish and the Yellowfin Tuna.

Section 6

Tigpanalipod sa Kadagatan

Heroism at the Frontiers of the Island

There is a call for fisherfolk to be considered as food security frontliners, as they are one of the key food providers for an archipelagic country. This idea is borne out of the experiences we had during the recent pandemic.

Attributing heroism, agency, and identity to fisherfolk are not new. Rather it is often an overlooked notion, especially in a country where fishing and fishing communities are common and plentiful. People are desensitized to the communities’ hardships and struggles. It is important that discourse and discussions are directed towards the improvement of the living conditions of our fishing communities; that opportunities and threats be identified through their lens; and for adequate solutions and ordinances be enacted for their benefit.

Everything that falls into the baloto belongs to the master of it, except that afterwards, all gather together and they give one of ten to the one who is the leader. Some, and this depends on their fortune, at times get a great quantity and some, nothing because not even one fish fell in their baloto. However, they are so courteous that they give a share to those who caught nothing so that on another day, the latter may give them something in return when their own short-lived fortune leaves, like those who had no success on that occasion.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. “History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period”. (Part One, Book 3) 2002.

Section 7

Mugnang Kinamot

Shellcraft and Cebuano Design

Cebuano creativity, ingenuity and resourcefulness do not only show in the building of their boats and their implements, or in the flavors of their culinary traditions. It is best seen in the elevation of ordinary materials to a thing of design and beauty. The wide variety of shells found in the seas of Cebu offers local artisans excellent materials they can use in decorating their bodies and their homes. The form, colors, and textures of these shells inspire them to create jewelry, embellishments to textiles, home decors and functional objects of specialized and everyday use.

Cebu City’s distinction as a UNESCO Creative City of Design celebrates the creative heritage of the Cebuanos. Contemporary Cebuano designers do not fail to pay tribute to materials that the seas have given them.

To relate all the differences in the multitude of various shellfish that are found in these seas, would be like wishing to count [the grains] of sand. Just as there are so many islands, large and small, shoals and reefs, beaches of firm sand and those of mud, which they call here anang: the very many rivers and streams which flow into the sea and over their sandbars which commonly are their beds, at one place large at another small, so one would be able to do extensive treatises on each. So, only of the more important and more prominent, be it for their delight in its flesh, which is greatly esteemed and diligently sought for, or because of the preciousness of the pearls that are found in them, shall we make a special mention.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 2) (2002).

-----

However, generally speaking, there can hardly be found a species or kind of shellfish or oyster which does not grow its pearls of greater or less fineness, bigger or smaller ones, with greater or lesser abundance, except for the very common ones of little worth. We shall treat the more precious ones which yield margaritas or pearls and aljófares, which have considerable value and price, not less for their fine luster than for their medicinal properties.

Those which we Spaniards call oysters, the Bisayans here call tipay, and the Tagalogs, kapis. They are the shape of round oysters, more or less wide, according to the time they are left in their natural place in order to grow.

These oysters or tipay are of a material which, although very solid, is transparent. Not that the sun passes through, as in glass, but the light passes as through fine alabaster. It surpasses the latter in its smoothness and thinness. As a result, they make windows out of it here, which are used for glass in a curious manner. They are no less useful for defense against the numerous great winds that run their course here. It is better than glass for durability and firmness, for no matter how these windows or panes are shaken or bumped, these shells neither break nor falter. Ordinarily, they fashion them with great skill into squares and set these squares, which are about the size of the palm of a hand, according to their desires, in various laths of tough woods; either in white like the molave, or red like the barayongs or naga or black, like ebony. They come out very well and beautify a room or gallery, which they are accustomed to circle with this kapis. And thus, they leave the room even10 in stormy and rainy weather with sufficient light for domestic tasks.

They also make lanterns, lamps or lights out of them wherein they protect the flame lest the wind blow it out; they are very bright and although perhaps the smoke may obscure them, with polishing they become like new.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 2) (2002).

The bounty of the land and sea in Cebu is not taken for granted, as the Cebuanos utilize every part of their harvest. They are known for their ingenuity and have turned even shells from the ocean into stunning crafts and designs.

(Photo)

One particular art form is called “lagang”, which involves cutting nautilus shells into pieces and arranging them into intricate patterns to create a unique piece of artwork. This technique is popular in Bantayan and Olango islands, where the people have perfected the craft.

In the past, Bantayan island was famous for its coral and shell crafts. Unfortunately, destructive fishing methods have caused damage to the marine ecosystem, resulting in the decline of the industry. However, there are still a few places where you can find ornaments made from various kinds of shells.

One example of a stunning shell craft is the shell curtain. Hanging these curtains on your doors, windows, or as room dividers can instantly give your space a whimsical beach vibe. The shells sway gently in the breeze, creating a calming effect and adding a pop of color to your room. You can even use them as wind chimes when your windows are open. Although it takes time and effort to make shell curtains, the end result is worth the effort.

Another magnificent item that Filipino artists have created from nature is the shell chandelier. The intricate design and painstaking craftsmanship that goes into making one of these pieces is truly impressive. Whether as a gift, souvenir, or decor for your space, a shell chandelier is sure to make a statement.

When making crafts from shells, there are various kinds which are used, such as kulis-kulis, sikad-sikad, scallop, bubbles, buwan-buwan, tuway-tuway/litob, lapas, tidlusan, nasa, binga, sigay, tamilok, buktot-buktot/bundok-bundok. These shells can also be used to make unique bags and purses, adding a touch of nature to your accessories.

In Cebu, the land and sea provide endless possibilities for creative expression and resourcefulness. Nothing is wasted, and everything is turned into something beautiful.

Section 8

Taob sa Pag-tuo

Surging Tides of Faith

The vastness of the sea, the calm and the chaos that characterize its movements, and the unfathomable depth of the underwater, instill spiritual and mythic qualities of the sea that affect the way Cebuanos embrace the mystical and divine. Fisherfolk pay homage to what they believe as sea dwellers, creatures that overlord the affairs of the sea. Launching new fishing boats necessitates tribute offering to these mythical creatures. A ritual of incensing the boat and its owners includes the gathering of plants that stick on one's clothing as a symbolic metaphor of abundant catch as fish is said to stick on the fishing nets. The spiritual world of the sea is very much a part of local folklore and belief systems.

With the introduction of Christianity, the waters of Cebu have been associated with a dance ritual that honors the Santo Nino (Holy Child Jesus). The dance movement of the Sinulog mimics the movement of the waves as it reaches the shore and recedes to the sea. Now a world-famous dance festival, the Sinulog continues to celebrate the lasting relationship of the Cebuanos with the sea.

Although they did not know who He was, they thought that He was much more than a mere man, because they acknowledge and understood that man did not make himself but that he was made by another. Yet, as we have already stated, they gave such a low beginning to the first man and woman, as if they were two coconuts or two knots of bamboo. Nonetheless they affirmed that this was the work of Someone who existed before them.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 3 Title) (2002).

-----------

These paglihi of theirs were so numerous that, if they observed them all - and they kept them better than they do the feast days today - they would have to pass the greater part of the year without working. Hardly would they perform any human action of some importance in which they did not observe some paglihi. Hence, this is the central meaning of this term lihi.

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, Cantius J. Kobak, and Lucio Gutierrez. "History of the Bisayan people in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period." (Part One, Book, 3) (2002).

-----------

Even in the spiritual realm, the common baroto was used for a divination activity called kibang, in which occupants would sit perfectly still in the middle of a boat and the diwata (sacred spirit) would answer by rocking it.

Funtecha, Henry F. "The history and culture of boats and boat-building in the Western Visayas." Philippine quarterly of culture and society 28.2 (2000): 111-132.

As the waves crash against the shore, the people of the coast know that the sea is not just a body of water. It is a living entity, a force that holds mystical power and consciousness. For generations, the locals have held onto their beliefs and traditions to honor the ocean and ensure its protection.

Their practices have blended with Christianity, brought to the coast through colonization and mission work. Over time, they've created a beautiful blend of worship that celebrates both the sea and the Christian faith. As the sun sets, the coastal communities gather to perform their rituals and ceremonies. Offerings are made to the ocean spirits, and prayers are said to Christian saints.

These syncretic forms of worship are a testament to the enduring spirit of the coastal people. They've faced numerous challenges, from natural disasters to the harsh realities of life as fisherfolk. But their faith and spirituality have remained steadfast, through their unique blend of beliefs and practices, they honor and protect the ocean that gives them life.

The fusion of indigenous beliefs and Catholic faith is also evident in the fiestas or festivals where fluvial parades are carried out. The most famous of these civic celebrations re-enact the arrival of Magellan's galleons bringing the image of the Santo Niño in the island of Cebu. The parade incorporates both Christian and pagan elements and is a testament to the unique blend of cultures in the Philippines.

Across the country’s different regions, there are many other unique rituals and practices.

In the three island communities, “palina” involves smoking various types of leaves and grass for purification and bathing of new fishing equipment or boats to attract good luck. In Bantayan, a meriko, or shaman, who conducts the ritual repeats, “Pamahawa mo mga dimalas, sulod ang de-bwenas” seven times. This is translated to, “Away with you bad luck, enter good luck.”

Palihi involves using anything that brings good luck, such as bathing new equipment or boats with liquor to attract fish, or dropping animal blood on them to avoid accidents. Although specific meanings and significance of the items and materials used in palihi are lost, these rituals are still observed as these are all knowledge passed down from their ancestors.

The practice of offering to the sea is also present in the three islands. In Hilotongan island, Bantayan, this is referred to as “haring”, an annual ritual obligation offering to the taga-dagatnon, or what they would refer to as sea folk. Often, this is conducted by the meriko, or shaman, wherein he would call, “Mga gingharian sa kadagatan, ari na ang pagkaon nga giandam ni (name of the person who asked for a ritual) (Kingdoms of the sea, here is the offering of…)”, before the offering is then thrown at sea. The beginning of the ritual obligation is marked by the first launch of the boat.

In Badian, this is referred to as “bayad-bayad”, an exchange ritual uncommonly practiced for fear of its exchange. It is believed that when this ritual is done, something horrible is bound to happen to the practitioner and his family after a few years, as a payoff.

Olango’s ritual offerings is closer to the Christian practice. They conduct “halad” rituals. Biko, a glutinous rice delicacy, is offered to the sea when a new boat is launched. Eggs and biscuits are offered on a full moon as a gesture of thanks for the bounty.

These rituals and beliefs speak of the deep connection that people in the Philippines have with the natural world. They reflect the unique blend of cultures that exist in the region and offer a glimpse into the rich history and traditions of the islands. It is a beautiful reminder that there's more to this world than meets the eye, and that we can learn so much from the traditions and practices of the past in order to understand our identities and histories.

Section 9

Pag-amping, Pag-andam

Challenges of the sea

Dagat ug Panagat: The Inseparability of Culture and Nature

Ian Dale B. Rios

Panagat as a Foundational Filipino Cultural Heritage

Contrary to the notions of modern contemporary society, panagat is not a mere economic activity handed down from the previous generations; it is a cultural heritage that bears the identity of our forebears and the relationship they have had with their archipelagic world (Rios 2022); which evidently continues to sustain coastal communities today.

Culture x Nature

The integrity of our local maritime cultural heritage does not only exists in the consciousness of the heritage bearers—our local traditional fisherfolks—but also on the physical space where they interact with the natural elements that define the sea (Rios 2020). Thus, “mistreating the integrity of the marine ecosystem fundamentally dispirits traditional fishing ways” (Rios 2022). And as Tauli-Corpus (2010, 6) points out that, “the loss of flora, fauna and microorganisms and the destruction of ecosystems are not just physical losses”. This also means the loss of indigenous knowledge systems, culture, languages, and our identities.” Certainly, it is a relationship that demonstrates the inseparability of culture and nature.

Kahimtang: Cultural and Ecological Conditions/Impacts and Discontinuation

Our very own local fisherfolks—the knowledge holders and the traditional occupiers of the sea—are aware that the abundance of aquatic resources has now been reduced to a mere memory. It is their lived experience. Technological advancement of modern fishing equipment and its associated methods have also efficiently enabled large-scale fishing vessels to massively harvest aquatic resources. “It has not truly alleviated the declining fish resources, nor has it provided sustainable solutions to the depleting fish stock in local environment” (Rios 2022), and those affected the most are the small-and-medium-scale fisherfolks. Moreover, the influence of modernized education has demoted traditional fishing ways as only for the uneducated and the undeveloped that is fated to remain at sea—a socioeconomic construct that marginalizes local fisherfolks as lesser members of society (Rios 2020). This is a demoralizing condition that displaces the local fisherfolks from their traditional economic space, pushing their traditional fishing ways to the margins. Such is a fundamental threat to the continuity of the local maritime cultural heritage.

Karon: Who Cares?

The sea is not a just a mere Instagrammable space; the beach is not just a nice backdrop for Facebook Profile Pictures; and a bangka or baroto is not just an object of display that you can easily take a photo with for your social media stories. These are also natural and cultural elements that comprise an integral part of the lifeways of the early Filipinos who had helped chisel the foundation of our archipelagic nation.

They deserve more than being exhibited. In a society with an undernourished identity, we need to place them to where they rightfully belong: at the forefront of an integrated development that is multi-faceted, which includes all sectors, especially those at the margins.

Considering the ecological challenges we face today, “[t]he integration of cultural heritage values into current resource management practices, environmental policies and educational programs only multiplies conservation significance” and will provide a comprehensive basis in managing coastal resources and resolving conflict of resource use (Rios 2022).

Now, the continuity of our own maritime cultural heritage is up to us, either we keep the bangka floating and sailing, or leave it to sink into the depths of an environment neglected by decay.

But who cares these days anyway?

Truly it’s now up to us.

Onsite Exhibition

SAULOG: ENCOUNTER, PILGRIMAGE, AND TRANSFORMATION

SAULOG: ENCOUNTER, PILGRIMAGE, AND TRANSFORMATION, An exhibition of faith, art and fashion by Steve de Leon.

Event

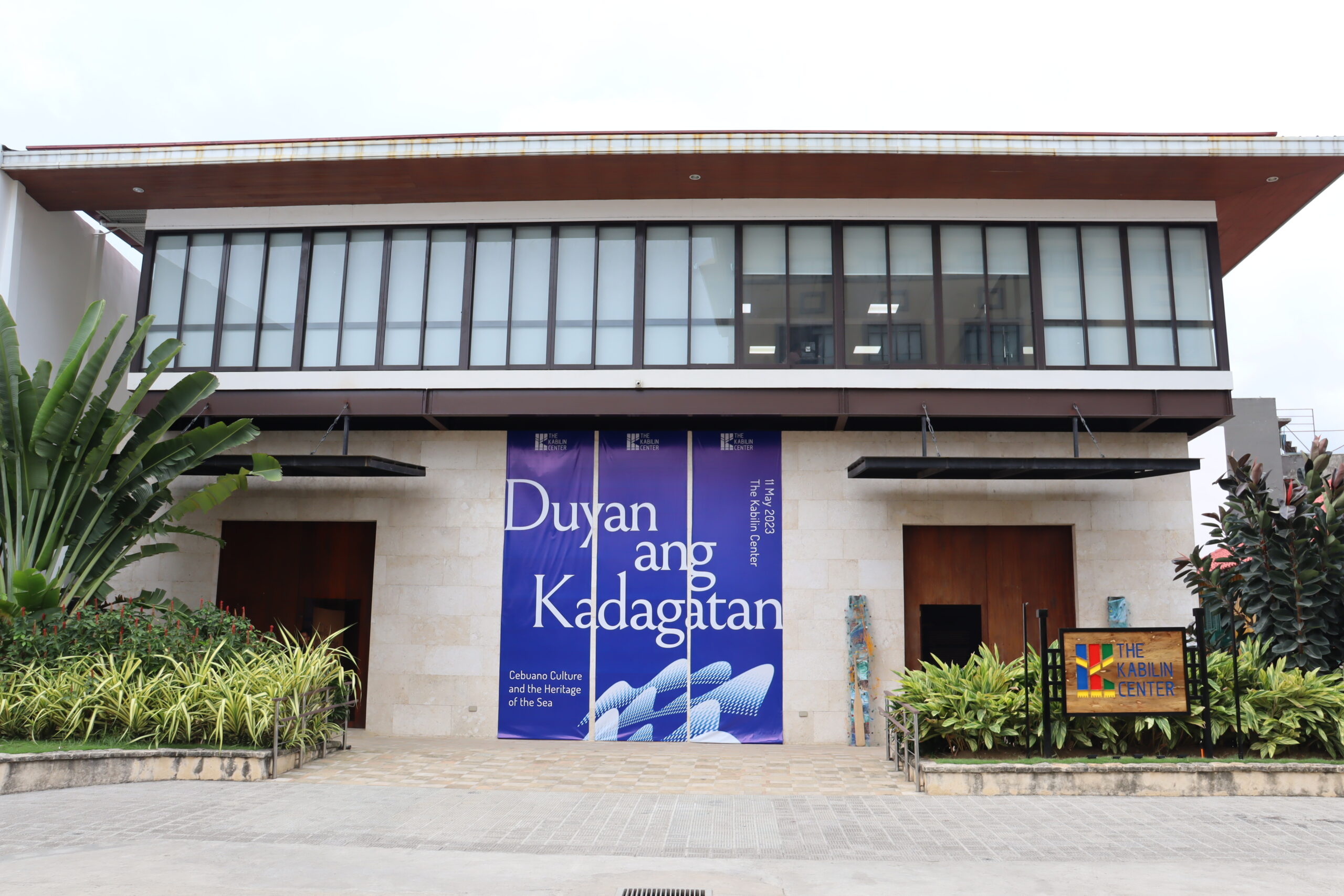

Badian Fisherfolk visit TKC’s Duyan ang Kadagatan (Cradled by the Sea) Exhibit

TKC was recently visited by one of the communities that we reached out to gather insights on different fishing techniques, traditions, and superstitions, which would later be featured in our exhibit.

The President and some members of the Zaragosa Multi-Purpose Cooperative were finally able to see their contributions inside The Kabilin Center.

The President and some members of the Zaragosa Multi-Purpose Cooperative were finally able to see their contributions inside The Kabilin Center.

President of the Zaragosa Multi-Purpose Cooperative is Ignacia “Yciang” Fabracuer and fellow member is Vigil Pepito who were asked to do an interview on their thoughts on the exhibit – Duyan Ang Kadagatan (Cradled by the Sea) Exhibit.

BOOK NOW! You can experience Duyan Ang Kadagatan (Cradled by the Sea) Exhibit, which showcases Cebuano Culture and Heritage of the Sea, when you visit The Kabilin Center! For bookings or inquiries, you may message us on FB or contact (032) 511 – 2665.

Onsite Exhibition

Online Exhibition

DUYAN ANG KADAGATAN (CRADLED BY THE SEA): Cebuano Culture and the Heritage of the Sea

Duyan Ang Kadagatan, or “Cradled by the Sea”, is a community exhibit that will focus on the relationship between bodies of water to the communal life of the Cebuano fisherfolk. The exhibition aims to pay close attention to a neglected aspect of Cebuano culture – the role of water to the life of Cebuanos.

The exhibit features artifacts and implements gathered by the fishing communities of Zaragosa Island, Badian, Olango Island, Lapu-Lapu, and the islands of Bantayan to show the interrelations of how the waters of Cebu have shaped the identity of Cebuano fisherfolk and Cebuanos as a whole.

Duyan Ang Kadagat encompasses the values, beliefs, practices, livelihoods, language, and knowledge that are attached to the waters that surround Cebu. It is the hope of this exhibit that you leave with a renewed appreciation for our local mananagat. An understanding of the interrelation between culture and nature, and to leave you in awe of our own Kadagatan.

The exhibit opened on May 11 for private viewing while Gabii sa Kabilin Ticketholders viewed the exhibit for free on May 12. Visitors from May 13 to September 11 will need to pay the Php 150 as entrance fee.

“It is the hope of this exhibit that you leave with a renewed appreciation for our local mananagat and to leave you in awe of our own Kadagatan,” exhibit guest curator, Jay Nathan Jore, said.

The event marks The Kabilin Center as a new player in promoting Cebuano culture and heritage. Owned and managed by the Ramon Aboitiz Foundation Inc., The Kabilin Center, is positioned as a hub for Cebuano culture; a source for credible content and creative experience and a center for connection and collaboration that brings pride to Cebuanos.

Event

THE KABILIN CENTER OPENS AN EXHIBIT ABOUT CEBUANO HERITAGE OF THE SEA

The Kabilin Center officially launches as a “hub for Cebuano Culture” as they open the community exhibit: “Duyan Ang Kadagatan (Cradled by the Sea): Cebuano Culture and the Heritage of the Sea” on May 12, 2023 at The Kabilin Center.

The exhibit titled “Duyan Ang Kadagatan” showcases the vital role and significance of the waters enveloping the island of Cebu in the lives of Cebuanos throughout history, and its profound impact on the region’s culture. The exhibit will highlight actual artifacts, such as boats and fishing implements, artworks, installations, and crafts, from fishing communities in Cebu–Zaragosa Island, Badian, Olango Island, Lapu-Lapu, and the islands of Bantayan–accompanied by historical narratives, anthropological descriptions, and literary texts.

The exhibit encompasses the values, beliefs, practices, language, livelihood, and knowledge, all carried and cradled by the bodies of water that are in Cebu.

The exhibit will open on May 11 for private viewing while Gabii sa Kabilin Ticketholders can view the exhibit for free on May 12. Visitors from May 13 to September 11 will need to pay the Php 150 as entrance fee.

“It is the hope of this exhibit that you leave with a renewed appreciation for our local mananagat and to leave you in awe of our own Kadagatan,” exhibit guest curator, Jay Nathan Jore, said.

The event marks The Kabilin Center as a new player in promoting Cebuano culture and heritage. Owned and managed by the Ramon Aboitiz Foundation Inc., The Kabilin Center, is positioned as a hub for Cebuano culture; a source for credible content and creative experience and a center for connection and collaboration that brings pride to Cebuanos.

Event

National Museum and Freedom Park join Gabii sa Kabilin

The soon-to-open National Museum in Cebu, located near Fort San Pedro and Plaza Independencia, and Freedom Park in Carbon District will be joining Gabii sa Kabilin on October 21, 2022, from 6 p.m. to 12 midnight as featured sites.

Although the National Museum in Cebu will not be operational on the day of the event, it will be mounting a special exhibit on the history of the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) along with a sneak peek of the museum’s future galleries.

The museum’s exhibit will also include findings from NMP’s archaeological excavations all over Cebu province since 1985, and an interactive display of archaeological objects and artifacts for children.

In 2019, after being housed in Museo Sugbo, the NMP found its new home in Cebu with the conversion of the Malacañang sa Sugbo (former Port of Cebu Customs House) as the new National Museum, thus strengthening and completing the agency’s presence in Central Visayas.

The NMP signed a usufruct agreement with Cebu Port Authority on December 13, 2019, with approved funding from the Tourism Infrastructure and Enterprise Zone Authority (TIEZA) of the Department of Tourism. The rehabilitation of the century-old building commenced in 2021 and is set to be turned over to the NMP before the year ends.

Gabii sa Kabilin participants can also learn more about Freedom Park’s historical and cultural significance through an exhibit at the Senior Citizen’s Park beside Sugbu Chinese Heritage Museum.

The special exhibit, mounted by Megawide subsidiary Cebu2World Development, Inc., will also feature conservation efforts and archaeological findings in the area. Freedom Park will be rebuilt on its original location as part of the historical commemoration of the Carbon District. Once a space for gatherings and freedom of expression, the park eventually became part of the public market.

This year’s Gabii sa Kabilin will feature 20 participating museums and heritage sites in the cities of Cebu, Mandaue and Talisay. For just one 200-peso ticket, participants will have access to the participating sites and their activities, unlimited bus rides and a complimentary tartanilla ride.

Initiated in 2007 by the Ramon Aboitiz Foundation Inc., Gabii sa Kabilin aims to celebrate Cebu’s rich heritage, cultivate a sense of identity and pride of place among Cebuanos, and help preserve local culture and heritage by encouraging Cebuanos to visit museums.

For more information and updates on Gabii sa Kabilin and the complete list of participating museums and heritage sites, visit www.facebook.com/gabiisakabilincebu.

Online Exhibition

Gabii sa Kabilin Online Exhibit

Learn more about the history of Gabii sa Kabilin-- its beginnings, the different themes